Sgt. Stubby

By John Reagan

August 12, 2010

A century ago, before there was Snoopy or Lassie or Rin-Tin-Tin, America read of the exploits of a true canine hero, Stubby, the only service animal given military rank in wartime duty, and whose exploits were saluted by presidents and prime ministers alike. When he died, the New York Times constructed a lengthy obituary approaching 1,000 words, writing that: "He was only a dog and unpedigreed at that, but he was the most famous mascot in the A.E.F. [He] took part in four major offensives, was wounded and gassed. He captured a German Spy and won more medals than any other soldier dog. He led the American Legion parades and was known to three Presidents. He was, indisputably, a fighting dog."

He was a Georgetown dog. And it all started on a football field far from the Hilltop.

In 1916, a small bull terrier was seen near the practice fields adjoining the Yale Bowl, and he learned quickly football's verities of endurance, falling into formation, and protecting one's teammates. Yale already had a mascot, of course, but the mutt was well known among the team and was called Stubby. Just over a year later, the same drill fields were serving as a staging area for the First Connecticut Regiment (102nd Infantry), heading to the War in Europe. Heading to Newport News, VA, someone snuck the loyal dog on the train heading south.

At Newport News, troops boarded ships for the long trip to Europe. What was a left-behind dog to do? It was then that J. Robert Conroy, a Yale undergraduate who joined the regiment, tucked the dog under his overcoat and quietly boarded the troop ship, with no one the wiser. The two became friends for life.

Where the regiment went in battle, the scrappy little dog followed, and served not only as a symbol of a simpler life back home, but a watchdog of uncommon bravery. Wrote the Times:

"The noise and strain that shattered the nerves of many of his comrades did not impair Stubby's spirits. Not because he was unconscious of danger. His angry howl while a battle raged and his mad canter from one part of the lines to another indicated realization. But he seemed to know that the greatest service he could render was comfort and cheerfulness. When he deserted the front lines it was to keep a wounded soldier company in the corner of a dugout or in the deserted section of a trench. If the suffering doughboy fell asleep, Stubby stayed awake to watch."

The dog gained additional fame in February 1918, saving the regiment when his howls gave warning of a German gas attack, though he was gassed in the process and suffered damage from shrapnel of hand grenades. Later during the battle, a German soldier had crossed the trenches under cover of night. Stubby recognized a stranger in his midst and promptly attached his bull terrier's teeth on the German's posterior, awakening the Americans and allowing them a unusual capture that made headlines across Europe.

The dog gained additional fame in February 1918, saving the regiment when his howls gave warning of a German gas attack, though he was gassed in the process and suffered damage from shrapnel of hand grenades. Later during the battle, a German soldier had crossed the trenches under cover of night. Stubby recognized a stranger in his midst and promptly attached his bull terrier's teeth on the German's posterior, awakening the Americans and allowing them a unusual capture that made headlines across Europe.The dog was recognized for heroism on the battlefield and given the three stripes of a Sergeant; never before or since has a dog assumed such honors. The dog received formal medals from the U.S. and French armies, including the Wound Chevron, a World War I medal that would later become the Purple Heart. However amusing this may all seem in retrospect, the ability of an animal to warn soldiers of impending danger was not lost on U.S. officials, whose future development of the so-called "K-9 Corps" introduced the concept of service animals into the military and into civilian life.

Stubby was a celebrity of sorts in the weeks after the war, marching in the Armistice parade in Paris and met by President Wilson in Mandres-en-Basigny. Heading home, he was formally decommissioned from the regiment on April 20, 1919.

Stubby and Conroy would finish Yale but would soon be heading for a new home--Washington, where Conroy enrolled in Georgetown law school and served as an aide on Capitol Hill. There, the famous terrier was a must-see, and over the next five years Stubby would entertain three different presidents (Wilson, Harding, Coolidge) and a host of dignitaries.

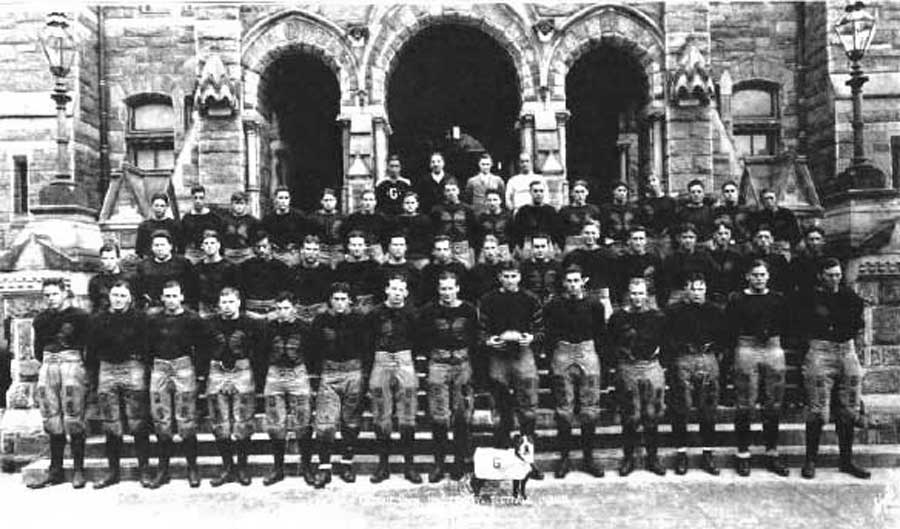

Stubby's duties at Georgetown were, by comparison, modest. He traded in the battle sweater of Chateau Thierry for a simple G sweater, appearing at home football games and pushing a football across the field at halftime. Stubby was afforded a place of honor--the front row--at each varsity football team photo.

The World War I veterans didn't forget the dog, however. The American Legion invited Conroy each year to its annual convention and parade, with the proviso that Stubby be allowed to march at its forefront. Hotels that forbade pets on the premises were more than happy to lift the ban for this honored guest.

"With the arrival of the District of Columbia delegation of the American Legion tomorrow will come the mascot of the A.E.F: Stubby, the dog hero of seventeen battles, who was decorated by General Pershing personally," wrote the the New Orleans Times-Picayune. "Stubby served with the Twenty-Sixth Division and saw four offensives, St. Mihiel, Meuse-Argonne, Aisne- Marne and Champagne Marne. The medal that was pinned on the dog hero by General Pershing is made of gold and bears on its face the single name "Stubby", and is the gift of the Humane Education Society, sponsored by many notables including Mrs. Harding and General Pershing."

"On parade Stubby always wore the embroidered chamois blanket presented to him by admiring Frenchwomen and decorated with service chevrons, medals, pins, buttons and a galaxy of souvenirs," said the New York Times. "On the end of his modernly bobbed tail a German iron cross was appended, the possession of which Stubby never explained."

"On parade Stubby always wore the embroidered chamois blanket presented to him by admiring Frenchwomen and decorated with service chevrons, medals, pins, buttons and a galaxy of souvenirs," said the New York Times. "On the end of his modernly bobbed tail a German iron cross was appended, the possession of which Stubby never explained."When Stubby died in 1926, no simple burial would do. The canine was stuffed and his remains sent to the National Red Cross Museum. In 1956, Conroy transferred his remains to the Smithsonian Institution, where he resides to this day, wearing the very medals that not only brought him fame, but recognized the lives he saved in the process.For Georgetown, it remains well represented by the bravest dog of his time--a true hero.