The Hometown Hero

By John Reagan

August 2, 2015

If walls could talk, the weathered bricks surrounding the high school stadium in Haverhill, Massachusetts would have more than a few tall tales.

In ninety-nine years, the small town stadium saw Babe Ruth taking batting practice, a pair of American Football League teams scrimmaging before thousands of local fans, and enough high school football dreams to fill its 100 yards and then some. But few would believe that its most memorable game over these years was that of its opening day.

Like many mill towns of New England, the early 1900's were its glory years. For Haverhill, forty miles north of Boston on the rail line to New Hampshire, it was the best of times as one of the nation's leading shoe manufacturing cities. With its idyllic public high school, Haverhill was the inspiration for the Archie Comics' Riverdale High, a stadium worthy of its stature was in order. In 1916, construction began on a 5,000 seat facility that would be the envy of the Bay State. But no ordinary high school game would be its debut.

Ten hours south by train, Georgetown University had never played a college football opponent north of New York in its 26 years of intercollegiate football. The Hilltoppers were a consistent winner among southern opponents, but many of its students (and recruits) hailed from New England. Following a 1915 season which saw Georgetown defeat North Carolina, North Carolina A&M (now N.C. State) and South Carolina by a combined score of 125-0, coach Albert Exendine sought to elevate Georgetown's standings by scheduling the nation's best of that era, the schools of what is now the Ivy League.

The "Big Three" of Harvard, Yale, and Princeton had dominated the sport for well over three decades by 1916, even as the Western (now known as the Big Ten) Conference was making inroads onto the national polls. Each of the three schools played in the largest stadia in the nation: Harvard's 30,000 seat stadium, built a decade earlier, the new 45,000 seat Palmer Stadium in Princeton, and the crown jewel, the 72,000 seat Yale Bowl in New Haven. By contrast, Michigan played at an 18,000 seat facility known as Ferry Field, while Notre Dame's Cartier Field sat but 12,000.

Exendine, a protege of Pop Warner while playing at Carlisle, knew what fellow Carlisle star Jim Thorpe already knew: a game against the top teams could elevate a program overnight. It was Thorpe, after all, who scored all 18 points in an 18-15 upset of Harvard in 1911 which put Carlisle on the map and Thorpe a household name. Exendine didn't have a Jim Thorpe on his roster, but he had a rising young star which gave Georgetown a chance to be noticed.

Johnny Gilroy, variously cited as being born in 1895 or 1896, arrived in Washington in the fall of 1915 to its dental school, although Gilroy was far more interested in football than orthodontics. Gilroy's opening season saw the true arrival of Exendine's Warner-style offense, which focused on speed instead of scrums, with what would be termed an open-air approach to scoring. The G-men weren't invincible, falling to Princeton 13-0 in its first game against an Ivy opponent and a 10-0 game at Army on the West Point plain. But with Gilroy at right halfback, Georgetown routed the remaining seven teams on its schedule by a combined score of 317-7, with Gilroy setting an NCAA record that year with a 90 yard kickoff return versus South Carolina. The 7-2 record was GU's best in three years, and with a strong returning nucleus, Georgetown was capable of even better things.

Its southern location was of little interest to the Northern powers. Princeton would not return the game from 1915, nor Army. Princeton played all its games except Harvard and Yale at home, and saw no need to travel to Washington to entertain opponents--Rutgers, Syracuse and Lafayette all traveled to Palmer Stadium, and all went home with a loss. The Tigers' only setbacks over three consecutive seasons from 1914 through 1916 were to Harvard and Yale.

Georgetown needed opponents, however. Its opener would be on the road at Navy, but its next four games remained absent of serious competition. By the time the 1916 schedule was coming into place, a collection of smaller colleges such as Randolph-Macon, Albright, and West Virginia Wesleyan agreed to games with Georgetown--certainly little more than cannon fodder for Exendine's men. One of these, Randolph-Macon, cancelled its game late in the summer, forcing Georgetown to dig even deeper for an opponent, picking up tiny Eastern College of Manassas, Virginia, as an early opponent.

The local townspeople of Haverhill had an idea, however. It offered the new stadium as a site for a intesectional game between Dartmouth College, located three hours north, and Georgetown. History does not say if Georgetown was an active co-conspirator in getting the game in Haverhill rather than the college oval in Hanover, but it's probably a good bet. Haverhill was not only the home of its new stadium, but the home of its most decorated footballer ever: Johnny Gilroy, class of 1915.

Georgetown's 1916 season started off with a loss to Navy, but its 60-7 walkover of Eastern College (variously reported as 67 to 7 and 69 to 7) garnered minimal press, even in Washington. For its part, the Indians had already played four regional opponents by this time, with wins over New Hampshire (33-0), Boston College (32-6) Lebanon Valley (47-0) and Massachusetts (62-0). Dartmouth was led by the "Iron Major", Frank Cavanaugh, a Dartmouth man who had previously coached at Cincinnati and Holy Cross. Cavanaugh's teams were a combined 41-7-1 entering the game at Haverhill, its first neutral site game since it met Carlisle at the Polo Grounds three years earlier.

In that game, Dartmouth was a distinct favorite, but was upset by Carlisle. Exendine, who was an assistant coach for Warner in that game, planned a repeat performance.

The Georgetown yearbook, Ye Domesday Booke, picks up the story:

"All energies were bent during that week to rounding the team into form for its game with Dartmouth two weeks later, The Eastern game, which we won, 69-7, showed a team greatly improved over that which had faced the Navy, but still lacking the machine like style of play necessary to defeat Dartmouth. Eastern, much inferior in weight and coaching, was a pigmy in the hands of the Varsity and had we tried, the score could have been greatly increased.With Gilroy performing before his hometown fans, the Blue and Gray continued to dominate. Turnovers held sway late, but neither team could take advantage. a drop kick by Maloney extended the lead to 10-0 in the fourth quarter, but Dartmouth could come no closer. For the first time in Georgetown's football history, it had defeated a team from what would become the Ivy League, and would not do so for another 87 years.

"Though we looked forward to the Dartmouth game with hope, it cannot be said that we were by any means overconfident. Exendine drove his men hard during the remaining days before they left for Haverhill to meet Dartmouth. Scrimmages were held every afternoon, the line was coached in charging, the backs in line smashing and end runs, and special emphasis was laid on the formation of interference and the use of the forward pass. Then came the game with Dartmouth, dedicating the new Haverhill Stadium.

"On October 21, a squad of thirty journeyed to Haverhill, Massachusetts, for the big game of our schedule and one of the biggest games of the year," it continued. Georgetown faced the powerful veteran team from Dartmouth, with the latter a 3-to-1 favorite. This game had a double significance, as it marked the formal dedication of the Haverhill High School Stadium. The city was all set for the game. Dartmouth had a large representation of about 5,000 alumni and friends; Georgetown was equally represented by our New England alumni and Haverhill friends.

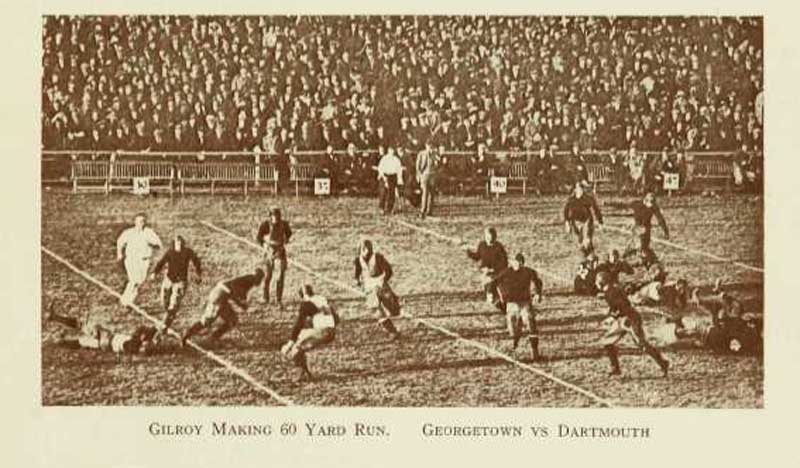

"On the first play Dartmouth kicked to [Jackie] Maloney, who was thrown on his 20-yard line. An attempted run...failed, and Maloney kicked. The Georgetown ends were very fast and nailed the Dartmouth men in their tracks. Captain Gerrish circled the end for a small gain. Dartmouth fumbled, and [Paul] Showalter recovered the ball on Georgetown's 46-yard line. Gilroy, after fumbling the ball on a poor pass, shook off four tacklers and ran 28 yards to Dartmouth's 27-yard line. It was the most brilliant exhibition of held running thus far, and the Georgetown stand expressed its delight. [Johnny] McQuade and [Pete] Wall gained a few yards on line plunges. The Georgetown stand s were rooting for a touchdown. On the next play, Gilroy made a beautiful pass on a fake kick that brought the ball to Dartmouth's 7-yard line... On [third down] Gilroy shot a perfect pass to [Tommy] Whelan, who caught the ball behind the line for a touchdown. Gilroy then kicked the goal. Score: Georgetown, 7; Dartmouth, 0.

"Dartmouth's most favorable opportunity to cross the line was offered in the second period, when Cannell, who had just entered the game, electrified the Dartmouth stand by tearing 40 yards down the field on a sweeping run around their left end before the speedy Gilroy brought him [down] on the Georgetown 6-yard line. Two rushes planted the ball two yards nearer the goal, but Georgetown's line was stiffening. The Dartmouth fans cried hard for a touchdown. The...Georgetown rooters yelled, "Hold 'em, Georgetown!" Coach Cavanaugh was scratching his chin. Exendine was smoking hard.

"Gerrish was given the ball and charged at our right tackle. Captain O'Connor was on the alert and hit the Dartmouth Captain so hard that the latter fumbled. Words cannot describe the few seconds that followed. Both stands were silent. Then Pete Wall emerged from the surging lines with the ball tucked securely under his arm. Three Dartmouth men tried to tackle him, but each was shaken off, and our Captain-elect, with a clear field to Dartmouth's goal, ran to his own 37-yard line, when he stumbled and was buried under an avalanche of Green players, who were in close pursuit."

Until 2015, it was the last time Dartmouth ever played Georgetown.

"The leading football writers of New England commended Coach Exendine for the perfect offense and powerful defense his team displayed," the College yearbook continued. E.B. Sargent, of the Haverhill Gazette: "It was Georgetown's greatest gridiron achievement in the college's athletic annals, and it cannot be said that the victory was not a deserved one. Georgetown clearly outplayed the lads from Hanover.

Albert J. Woodlock, of the Boston Globe, and C. F. Parker, of the Boston Post, congratulated Georgetown as having one of the best backfields in the country... The team was banqueted after the game and met at South Station, at Boston, by Mayor Curley, who congratulated each member of the squad.

Who is there that will ever forget that auspicious night when the glorious news of Georgetown's victory over Dartmouth by the score of 10 to 0 reached our ears? The next day Union Station was swamped with our turnout to welcome back home that wonderful team. With a rush that threatened serious damage to the grand and stately gateway to our National Capital, we bore our heroes to the waiting automobiles. That night the student body held a bonfire celebration, the like of which no resident of Georgetown ever witnessed before. It was the finest celebration of a victory ever held on the Hilltop."

The game elevated Georgetown's visibility in the national press alongside other Eastern powers such as Fordham, Syracuse, and Pittsburgh, beginning a run of over three decades of national coverage. Johnny Gilroy would end up leading the nation in rushing in 1916 and scored a record 160 points (20 touchdowns, 40 PAT's). At the end of the season he became Georgetown's first ever selection to the Walter Camp All-America team. It might not have happened without a homecoming game the likes Haverhill Stadium would not see again.